Awesome Alexanders

A neglected but powerful plant

Alexanders, also called Alisanders, Horse-parsley, Wild-parsley, and Black Lovage. Its Latin name is Smyrnium olisatrum which suggests it comes from Smyrna or modern Izmir in Turkey. Evidence of cultivation by the Romans dates to the 4thC BCE, and presumably before then in Smyrna and around the Mediterranean coastlines. Notice the rich and wide distribution in the UK.

Coastal distribution of Alexanders. 1

Other sources refer to its name as the Greek smyrrh a mythological woman (see below). The root of the word is Semitic. Others say the generic name Smyrnium is derived from the Greek word for myrrh and that the roots have a similar fragrance. Olusatrum was the Roman name, olus (herb) and ater (black). The English name, Alexanders, may be a corruption of the Latin. The name Alexanders may relate to its believed origin in Alexandria, Egypt. Others see a relationship both with the city Alexandria in Egypt and the Macedonian King Alexander the Great. As the map shows it grows in both those areas. Certainly, sailors knew of the plant’s anti-scorbotic actions and would collect it from coastal areas to supplement their diet. The earliest find of Alexanders in Britain is a seed found at a Roman site at Caerwent (Wales)2.

Description. Alisanders is an early flowering herb it grows thick and bushy up to 4 feet (1.2M) tall. It likes shady areas, like hedges and in coastal regions in southern Europe, it is often found on scrub lands growing with the bushy Vitex agnus castus (Chaste tree). It has large leaves divided into three leaflets, which resemble celery leaves, it is from the Apiaceae family. The flowers have yellowish umbels. It has a thick blackish root, white inside and smells sweet, but tastes bitter. The ripe fruit is black in colour (hence the other names). It is flowering now, in the South anyway.

****Alexanders may be confused with Hemlock Water Dropwort which is poisonous. ID details here here ***

Traditional Uses:

The flowers and roots were used for flavouring food, while the leaves and fruit had anti-scorbutic, stomachic, anti-asthmatic properties and was used for the gut, the urinary system and reproductive ailments.

Alexanders is one of the few fresh plants that can be eaten in February or March. In the west of Britain, it had a reputation amongst sailors of cleansing the blood and curing scurvy, and in Dorset it was known as helrut, which is possibly a corruption of "heal root" (or maybe the word means something else in Cornish). The seeds have also been used as a cure for scurvy. (see below for Ascorbic acid content). It fell out of favour in the 18th century after celery was mass produced to replace wild herbs and vegetables.

Culpeper wrote:

“This plant is under Jupiter, therefore friendly to nature. The whole plant has a strong warm taste and was more used in the kitchen than in the medicinal way, having been either eaten raw, as a sallad among other herbs, or else boiled and eaten with salt meat, or in broths in the spring season. The root pickled was deemed a good sauce…It is reckoned to be of the nature of parsley or smallage, but stronger, and therefore may be serviceable in opening obstructions of the liver and spleen, provoking wind and urine, and consequently good in the dropsy or stranguary. For this purpose, half a drachm of the seeds powdered, and taken in white wine, every morning, is seldom known to fail. It is likewise good for bringing on the courses, and expelling the afterbirth.”

***do not use in pregnancy***

Culpeper continues:

“This herb has a mixed sort of smell between lovage and smallage; about December and January the shoots appear above ground, which taken before the leaves spread and grow green, and boiled in a pretty large quantity of water, and seasoned with butter, are not only a very wholesome, but also a very pleasant-tasted spring food. The flower buds, and the upper part of the stalk in the beginning April, before the turfs spread, and the flowers open, are likewise very good, if managed the same way.”

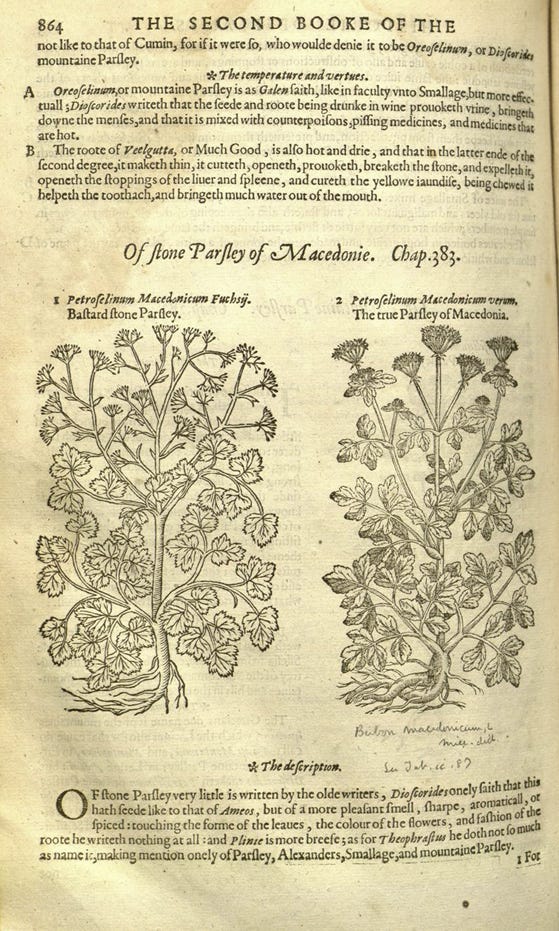

Gerard considers the seed and root hot and dry in the third degree and so are cleansing and drying to the body. The seeds ‘bring down the flowers’ meaning they bring on menstruation, they ‘break and consume wind’ ‘provoke the urine’ and are good for ‘strangury’ where there is a frequent need for urination with little or no urine being passed.

Gerald’s Herbal 1597.

A recipe by Caleb Threlkeld (early 18thC) for Irish Lent Potage includes Nettles, Alexanders and Watercress all early flowering herbs. Known as Baldiran or Göret in Turkey where the young shoots and leaves are cooked and eaten with yoghurt, or eaten fresh as a salad. The roots are also eaten cooked or fresh and are considered to be the best part of the plant, they are dug up during the winter, when the tubers are most fleshy. The seeds have a pepper-like taste. (Wikipedia)

Modern foragers would agree: ‘Eat Weeds’ has some great recipes here.

Mature fruits (schizocarps) splitting into two mericarps, revealing the carpophore between them. Alex Lockton 2022. CC-BY-SA 4.0.

Alexanders contains essential oil, flavonoids, Ascorbic acid and has antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and anti-parasitic actions.

Where the plant is grown affects its constituents: in Italy it contains fifty chemical constituents, furano-sesquiterpenes predominating in the flowers (59.1%). In England, isofuranodiene (curzerene) is the major furanosesquiterpene and is found in the root. The essential oil extracted from fresh aerial parts near Ajaccio, Corsica, contain isofuranodiene (21.7 %) while the dried fruits from Turkey contain glechomafuran and the leaves and fruits from Greece have high levels of curzerene (29 %) and furanoereemophile (28.7 %).

The essential oil contains variable amounts of sesquiterpenes, and monoterpenes have been identified as major constituents in regions including Italy, England, Turkey, Greece, Morocco, and Lebanon.

Sesquiterpenes are known for their hypotensive, sedative, and anti-inflammatory properties and are useful in medicine. The highest concentrations are seen in Italy (roots 45.8%) ripe fruits (26.7%) leaves (24.6%), in England, flowers (19.38%) roots (17.13%). While Curzerene content was highest in Italy, roots (39.7%), flowers (38.1%), Greece, leaves (29%), England flowers, (28.31%).

Flavonoids: the antioxidant action is probably due to the flavonoids, which have been shown to relieve oxidative stress-related conditions. Flavonoids possess radical scavenging properties and thus they reduce the production of free radicals. Other flavonoid-rich extracts from plants within the Apiaceae family, such as Petroselinum crispum, Apium graveolens, and Coriandrum sativum, show significant anti-inflammatory action.

Alexanders contains large quantities of Ascorbic acid, found in the largest quantities in immature green fruits, leaves, and flowers. Hence the tradition of eating leaf buds and new leaves in early spring when other ascorbic acid containing foods are scarce and scurvy may be an issue. Ascorbic acid also has therapeutic effects in conditions associated with oxidative stress. Ascorbic acid influences gene expression which may contribute to the plant's anti-tumour activity. Ascorbic acid is also anti-inflammatory.

Essential oils: research has shown a wide variety of theraputic actions of the essential oils. Furanodiene has been shown to have anti-cancer properties including: breast adenocarcinoma, colon carcinoma and glioblastoma multiforme. Isofuranodiene also has been shown to destroy cancerous cells by blocking the growth, invasion, and migration of new blood vessels in cancerous cells. Isofuranodiene also has anti-inflammatory actions and is hepatoprotective by mitigating the inflammatory response, protecting liver tissues from oxidative damage, and improving overall liver health. It also has a neuroinflammatory protective function.

[side note: Jupiter is the planet which shows growths, including cancerous ones as well as ruling the liver.]

Medicinal virtues:

Taken fresh in Spring as a cleansing tonic Alexanders is a great source of Vitamin C. It’s anti-inflammatory actions are used for stomach and kidney conditions. Its use in oxidative stress and potential anti-cancer herb, suggests it works at a deep level in the body. Traditionally, it was used in asthma, for menstrual problems due to sluggish circulation and as a hepatic. The leaves were used to treat wounds and scurvy, the fruit for the stomach and lungs, the juice of the root is laxative, diuretic and stimulates the appetite. The seeds are a rich source of protein and carbohydrate.

Magical Uses:

This is a very powerful plant. Use to calm down extreme states like frenzy, rage and terror and centre. It has dark, wild, female energy. Interestingly, the Greek name Smyrna relates to a myth where a woman of that name is cursed by Aphrodite to fall in lust with her father. She tricks him into having sex with her and becomes pregnant. When he discovers what she has done, he tries to kills her. She escapes to Arabia. The gods take pity on her and turn her into the Myrrh tree. The tree gives birth to Adonis, the ideal, beautiful man. The myrrh resin is said to be Smyrna’s tears. The deep rooted physical properties of the plant are mirrored in its magical and emotional uses. The festival of Adonis was celebrated in Midsummer and although this is a plant of Jupiter it presages the coming of high summer and the fire season with its fierce positives and negatives.

I will be talking about the Choleric Season in the final part of my Magical Herbalism series here

The Moon has much to say about our bodies, our emotions and our roots. Understanding our own personal moon and the passage of the Moon through the sky gives us insight into our nature. Details on the here and here

By Kaidor - Own work based on: Randall, R.E. (2003), Smyrnium olusatrum L.. Journal of Ecology, 91: 325-340. (Fig. 2)Map:Natural Earth (public domain) edited with Mapthematics Geocart and vectorized with Inkscape., CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=107867764.

Lyell, A.H. (1911). "Appendix on the vegetable remains from Caerwent". Archaeologia. 62: 448.